Palliative care. Before this week’s appointment, I had all kinds of preconceived notions about it. My knee-jerk assumption was that palliative care was for people who were in the active process of dying, i.e. in hospice or with a limited number of months to live.

My oncologist, however, assured me that palliative care was really more about taking care of the whole patient. Meaning: symptom management, pain management, diet, medications, and resources for counseling, etc. Palliative care had also been highly-referred by some of my most trusted family friends and top oncologists employed at centers of excellence.

Heading into the appointment, I was feeling better than I had in a long time. My cancer symptoms—the collapsed lung, the pain from the tumors pressing against my organs, the difficulty breathing, the coughing and wheezing—had all but subsided. The side effects from my treatment were rearing their ugly heads last week, but after a reduction in the dose of my medication, the muscle aches and joint pain began to let up.

My doctor’s positivity, her flexibility, and her assurance that I’m doing well had me floating. For a couple wonderful days, I was smiling freely and feeling some energy return, leaving the house, driving the car, going to social gatherings.

I felt nearly human.

On the Wednesday of the appointment, I readied myself with questions to discuss with the palliative care doctor. I wanted to talk about the similarities between patients who had overcome the odds and survived. What were they like? What did they do? Are there any patterns you can draw through them—even ones that may not be obvious? Give me scientific, raw data. Then give me whatever spiritual, unanswerable miracles that occurred. I want to hear it all.

I imagined we could zoom out and take a holistic view of all the medications I take: supplements, vitamins, prescriptions for allergies, asthma, depression, pain, plus the targeted therapy. Do I need all of these? What could be cut out? Or do I need different doses? Are there other meds I should avoid?

I wanted to hear information on how to increase physical activity with lung cancer. Did my doctor recommend yoga, rehabilitation, or walks to slowly get back into the swing of things? Did she have ideas for respiratory goals or other ways to measure heart and lung health?

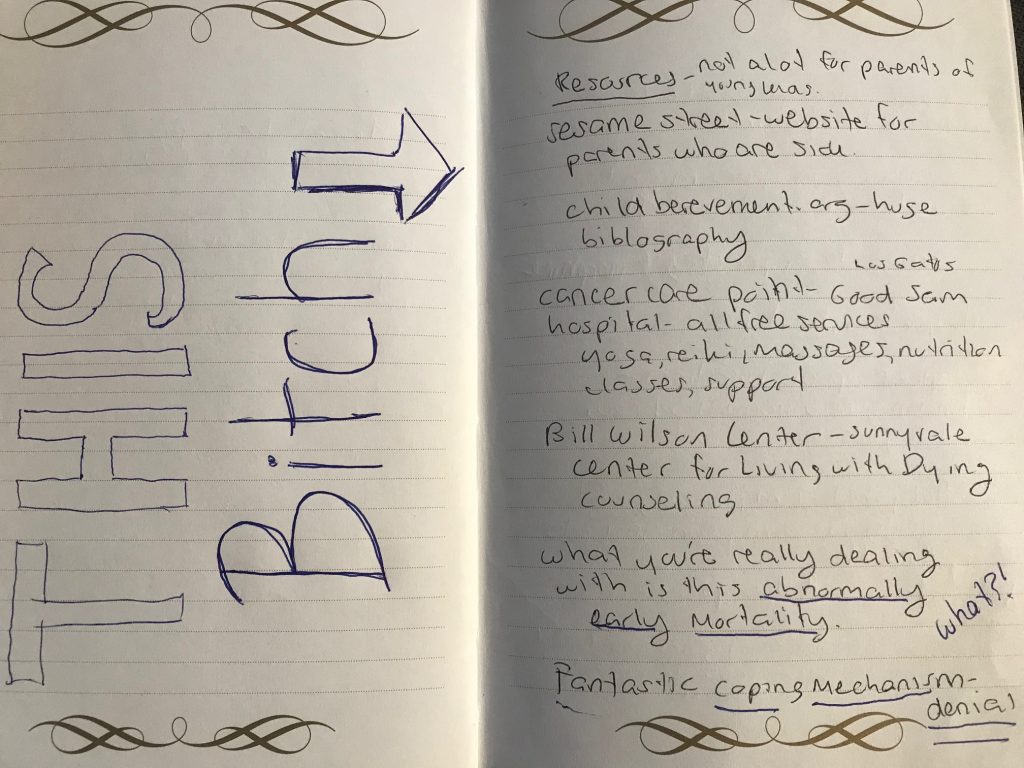

When I entered the appointment, I was met with a friendly, slightly frizzy-haired woman who looked me in the eye and spoke with a gentle voice. After a brief discussion about resources for counseling—and how there aren’t a lot of great options for parents of young kids—I was quickly warming up to the palliative care experience. However, it only took about 15 minutes and a couple of “ow, that stings” cutting remarks to realize something was off.

I should have known this was not going to go the way I wanted it to go when she mentioned a child bereavement site, the Bill Wilson Center for Living with Dying, and another cancer center for the terminally ill in quick succession. Each cheerful statement became soaked in malice when I realized that, oh no:

Palliative care is exactly what I thought it was going to be.

A caveat: If you’re dying in a couple months, this is absolutely the care for you. If you’ve had the “get your affairs in order” conversation, call up your health provider’s palliative care department. If you can see yourself sending your child to a class about the loss of a loved one, then what happens next won’t offend you.

But if you’re just one month into your treatment, feeling pretty decent, and on promising medication with a shot of at least a couple good years ahead of you, this is not for you.

If you’re not ready to roll over and accept a shitty “destiny,” then palliative care is not for you.

And if it’s a strong possibility that you will die but not an absolute certainty, and your palliative care doctor is fucking with your head, having only briefly looked at your file, then this particular bitch may not be the palliative care doctor for you.

Back to the appointment. I was feeling rather hesitant about all the dying talk, but things didn’t really start going downhill until Dr. Evil told me that “what you’re really dealing with is an abnormally early mortality.” Confused by the term, I asked her to repeat it. She did. She explained that it means an unusually short life and followed up with, “So what will you be doing, then, with the rest of your short life?”

Huh. That felt a little unnecessarily harsh.

I squinted my eyes and pursed my lips and retorted, “I plan not to have an abnormally early mortality.”

Devil woman replied. Her smile was not smug. She genuinely meant this.

“That’s good! Denial is a great coping mechanism!”

…this bitch.

Devil woman went on to tell me that she’d be happy to kick my ass out of denial in 2, 4, or 6 years when it’s necessary, and how she’s so sorry I won’t be able to see my son graduate high school. At this point, I’m just listening to her like:

And thinking of ways to destroy her.

But instead of snapping back, I felt defeated. Devil woman topped off the disaster of an appointment with a pamphlet on advanced care directives and sent me, bamboozled, on my way.

How can I move forward and truly believe I’m going to beat this thing when I now know I’m likely in denial? I know I probably don’t have a full life ahead of me, but I also truly believed I had a shot at one, albeit a long one. Am I in denial about being in denial? My happiness gets sucked behind a dark cloud of reality.

I go home. I have a good cry. And the next day, on wobbly legs, I take a deep breath and dig deep.

Dancing was damn hard, I think, and I took it on. The odds of making it are slim, and I had the beginnings of a nice career going before I was injured.

Becoming a professional writer: it’s pretty damn unlikely. It’s an uphill battle to get regular work, do it full time, and then get paid well enough to survive on it. I did all of those things. I’m still pressing every day to be better and better. I still love what I do.

I wasn’t sure if I was going to be able to have kids but I did.

I moved to California with two suitcases and one freelance assignment for love. I’m damn proud that I built a wonderful life for myself here after basically starting with nothing.

I’m sweating and I’m weak, but as I turn to face the dark cloud, my voice is steady.

Lady, you have no idea who you’re fucking with.

One thought on “The Devil Wears Palliative Care”